I first became aware of William Justema during my research for ‘Crossing the Threshold: The Frames of Florine Stettheimer’. (American Art, Summer 2025 39:2)

Among the Stettheimer Papers at Yale’s Beinecke Library is a 3-page typewritten letter from 1938 signed simply ‘Billy’. The return address does not specify the name of the sender. The letter is a defense of his frame designs in response to an apparent accusation from Stettheimer that he had plagiarized her original frames. Eventually I was able to identify ‘Billy’ as William Justema. It was an interesting journey into the artistic milieu of the 1930’s, his association with Carl Van Vechten and his occasional attendance of the salon of the Stettheimer sisters.

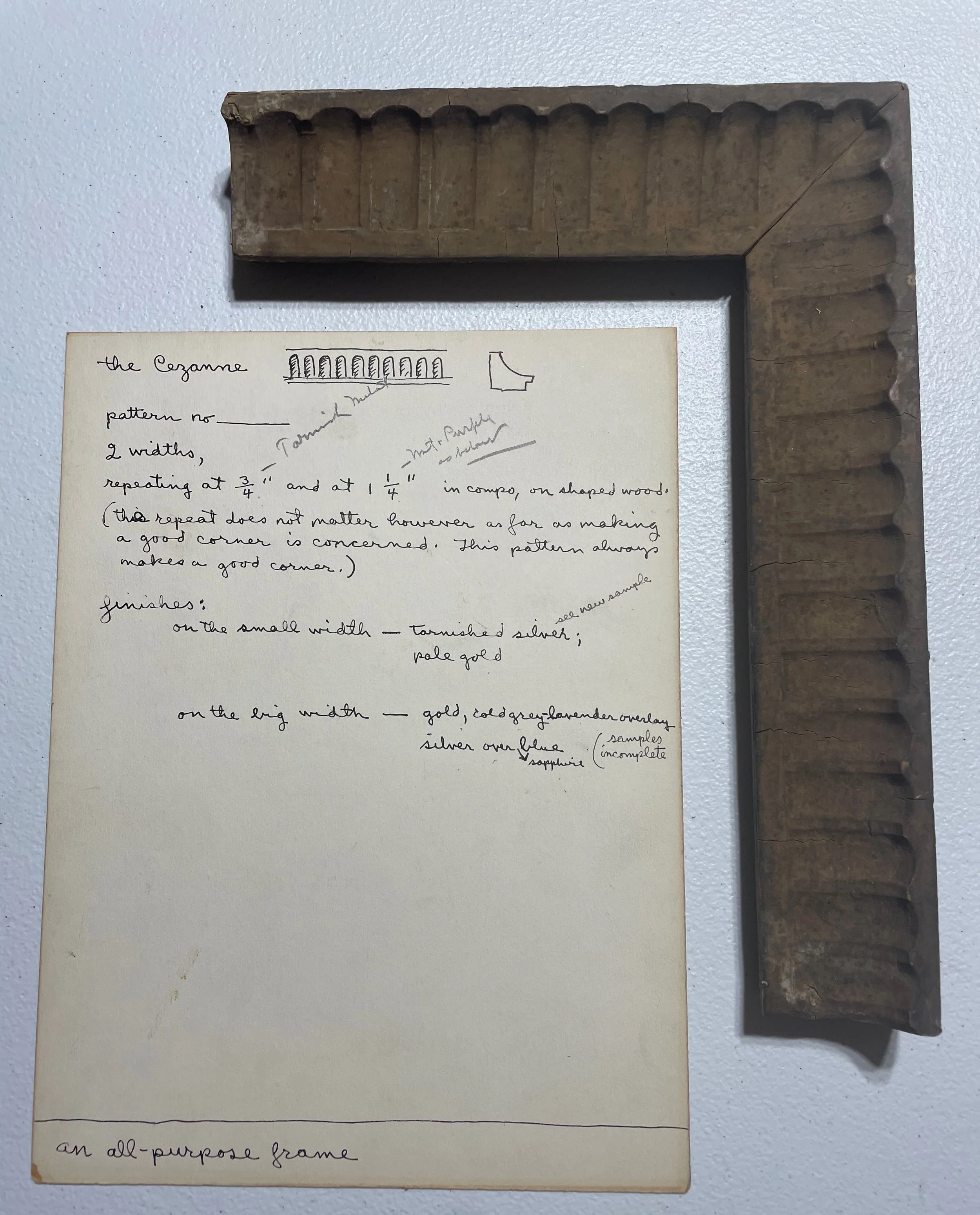

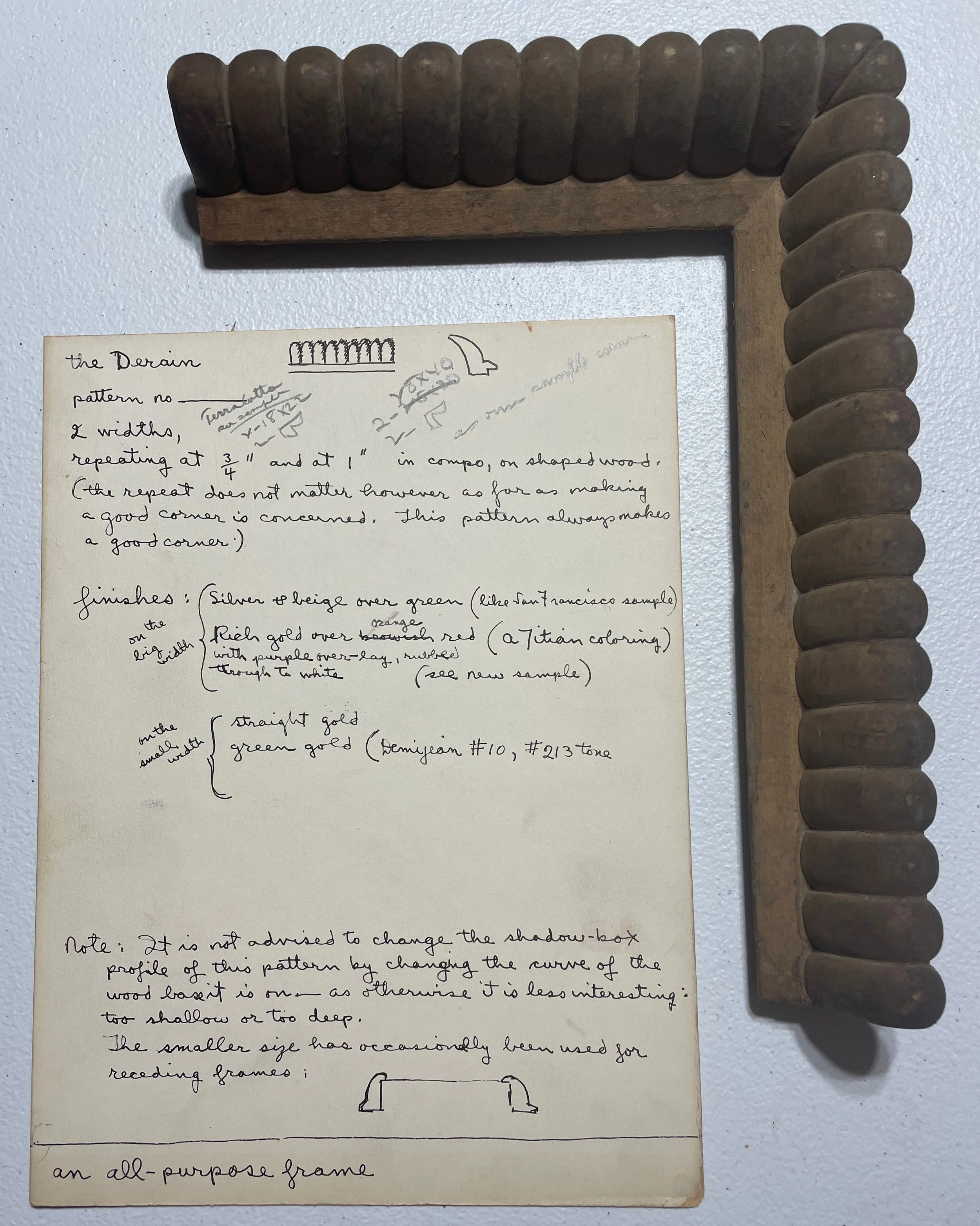

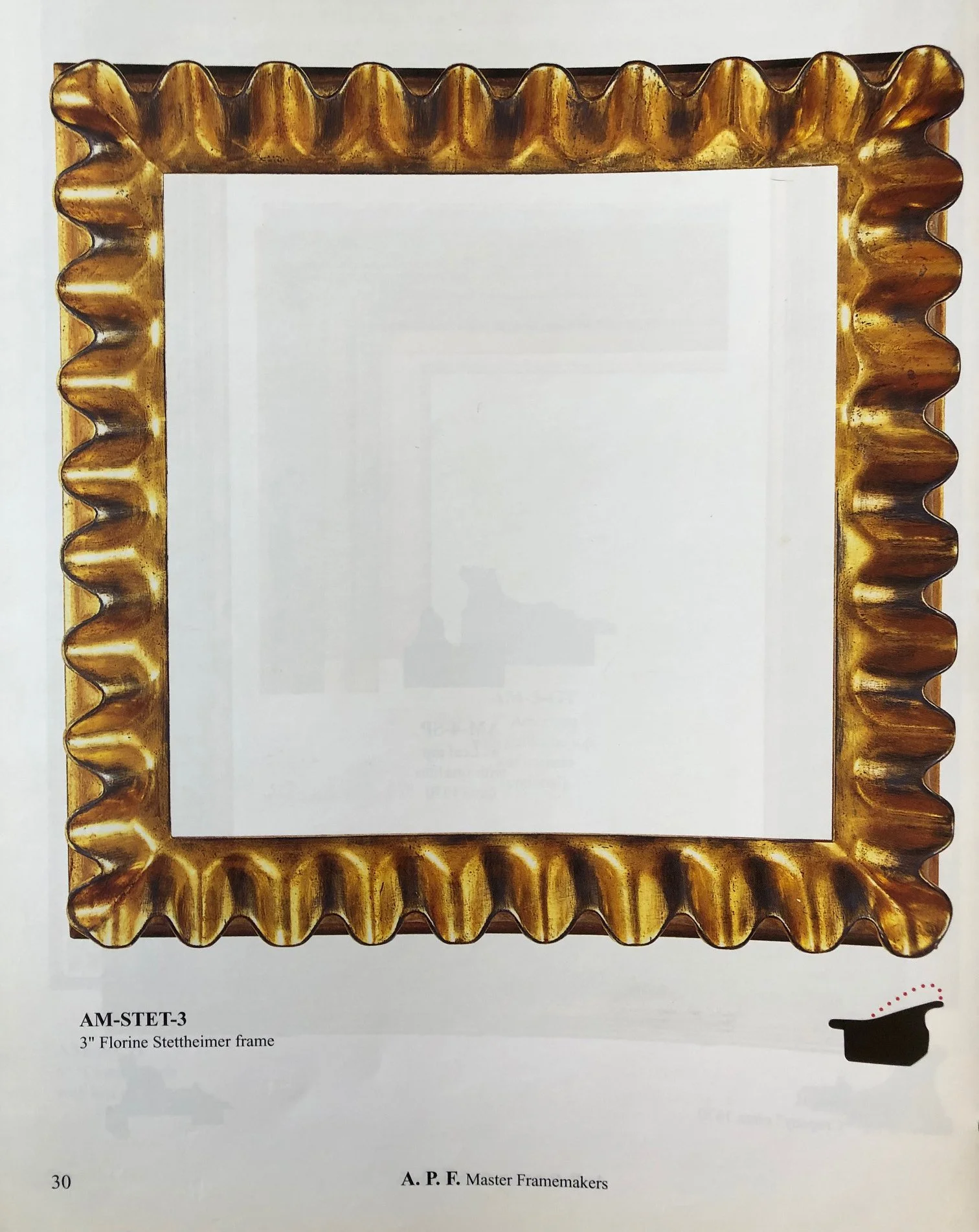

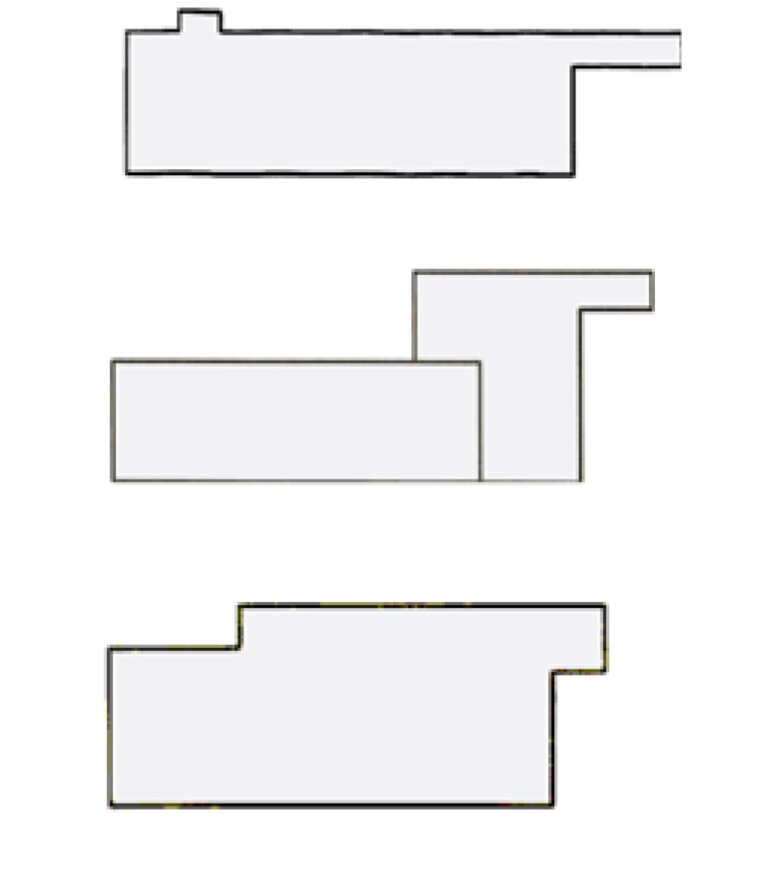

I discuss the encounter between Stettheimer and Justema in American Art and endeavor here to offer more information about Justema, his life, and his frame designs than the article allowed. In a magical serendipity I learned during my research that Justema’s frame sketches and the prototype models for his frame designs have survived and can be fabricated. [1] (These are discussed in the Part II blogpost about Justema and his frame designs.)

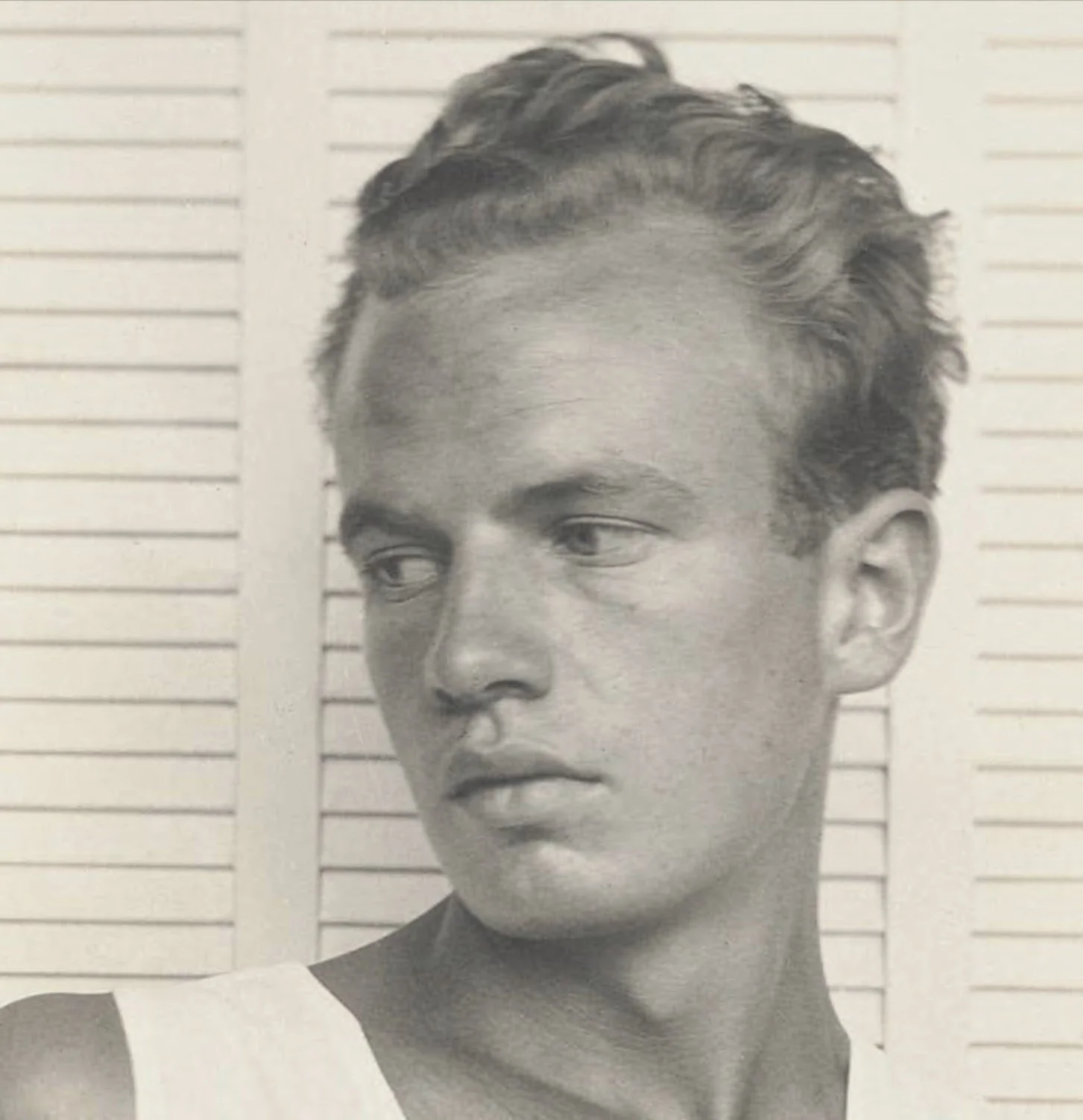

William Justema (1905—1987) worked in design throughout his life. Born in Chicago, he moved with his family to Los Angeles while in his teens and soon became a close friend of the photographer Margrethe Mather, with whom he collaborated on photos. When they first met, Mather was closely associated with photographer Edward Weston until he left for Mexico with Tina Modotti. [2]

Figure 1: Justema approximately age 17, photographed by Margrethe Mather, c.1922

He studied painting in the San Francisco area with Stanton MacDonald-Wright and Xavier Martinez. While in San Francisco around 1929-31 Justema worked as an “all around painter-decorator at M.H .de Young Museum which was being refurbished at the time.” During this time he was able to persuade the museum director Lloyd Rollins to show Mather’s work and he created a small exhibition of their collaborative photographs entitled ‘Patterns In Photography” that opened in July, 1931. (Many of these images are included in his book Pattern: A Historical Panorama (1976), New York Graphic Society, Boston, MA.)

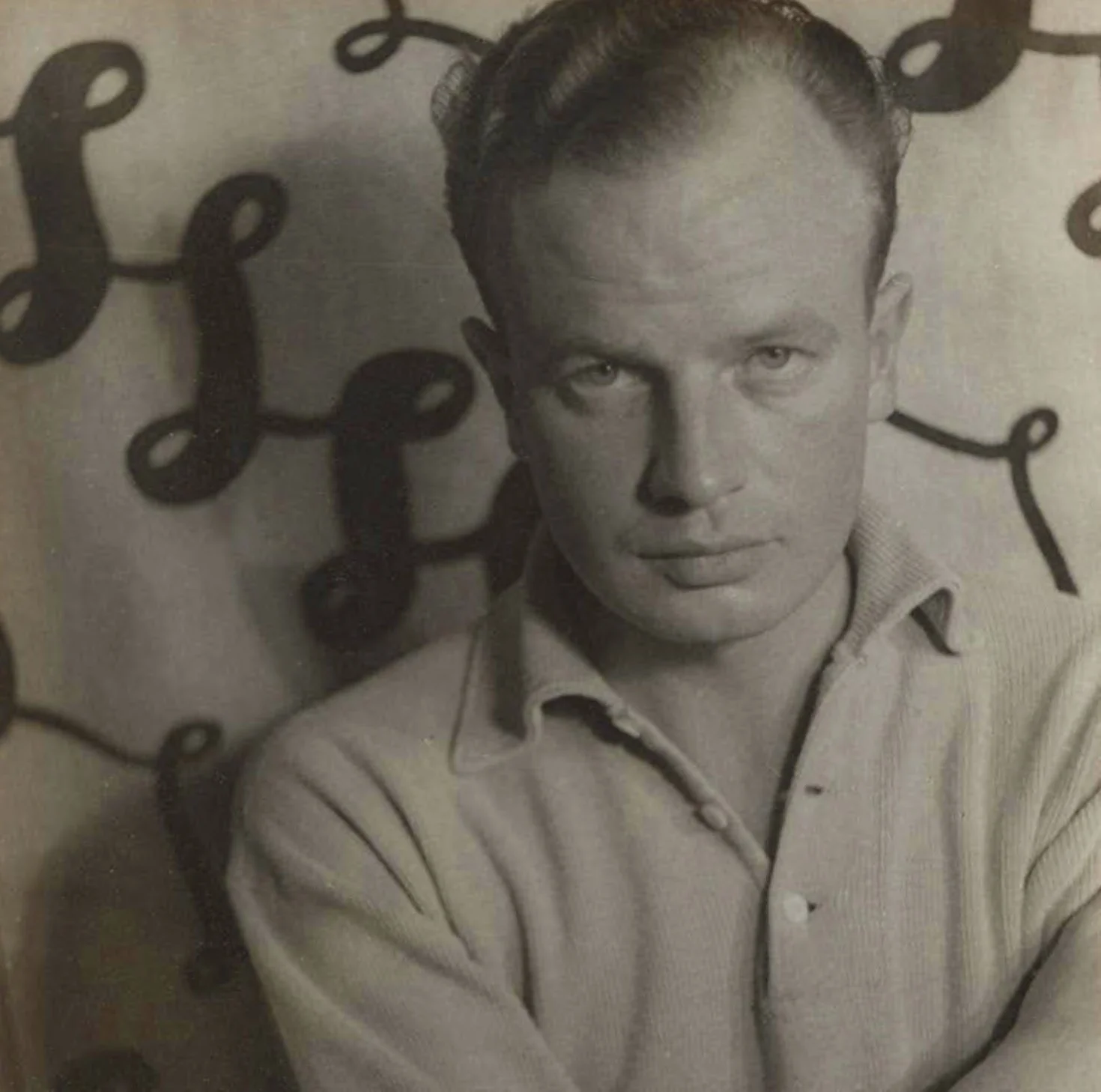

Figure 2: Justema with calla lilies, photographed by Margrethe Mather, c.1922

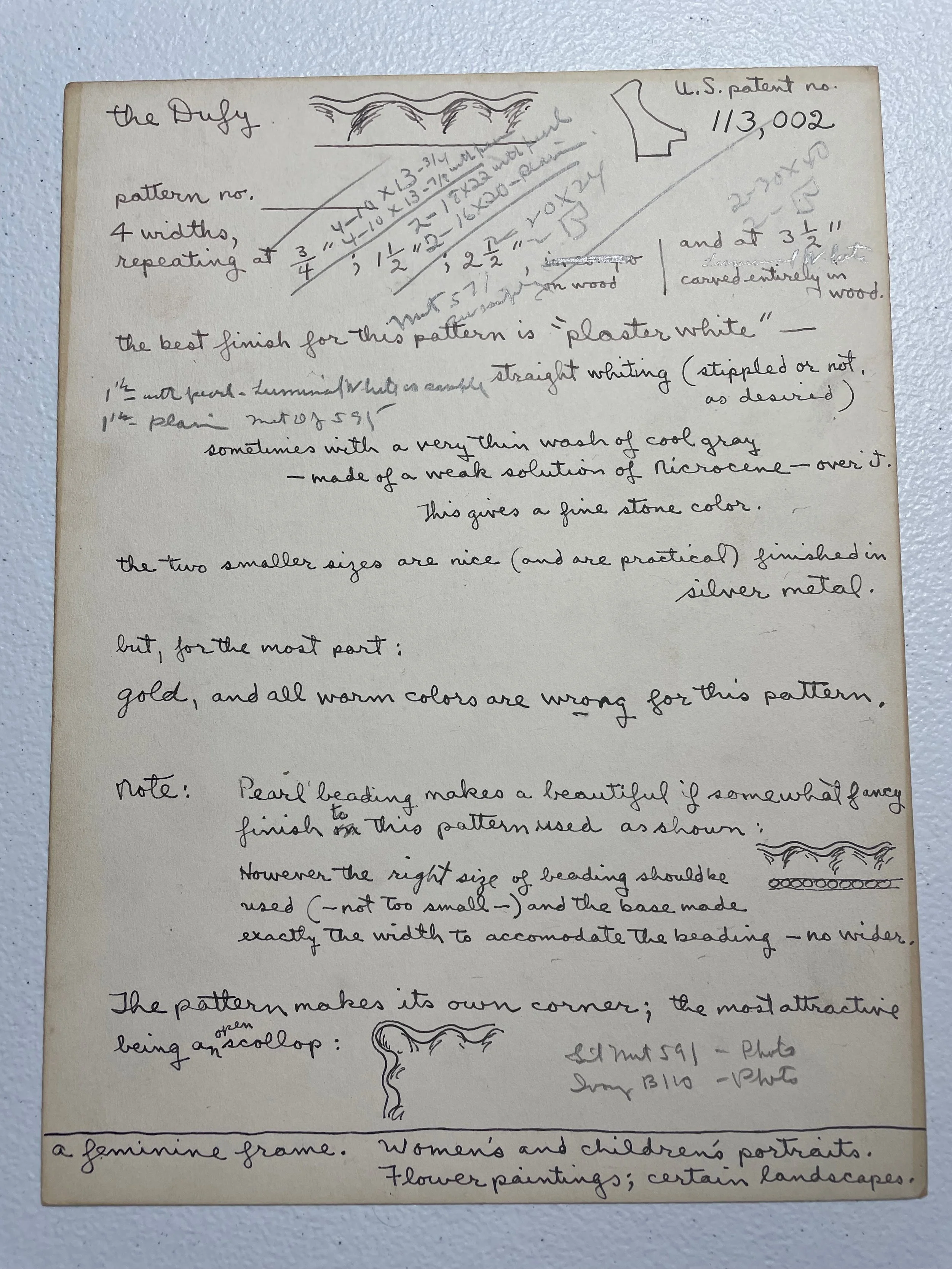

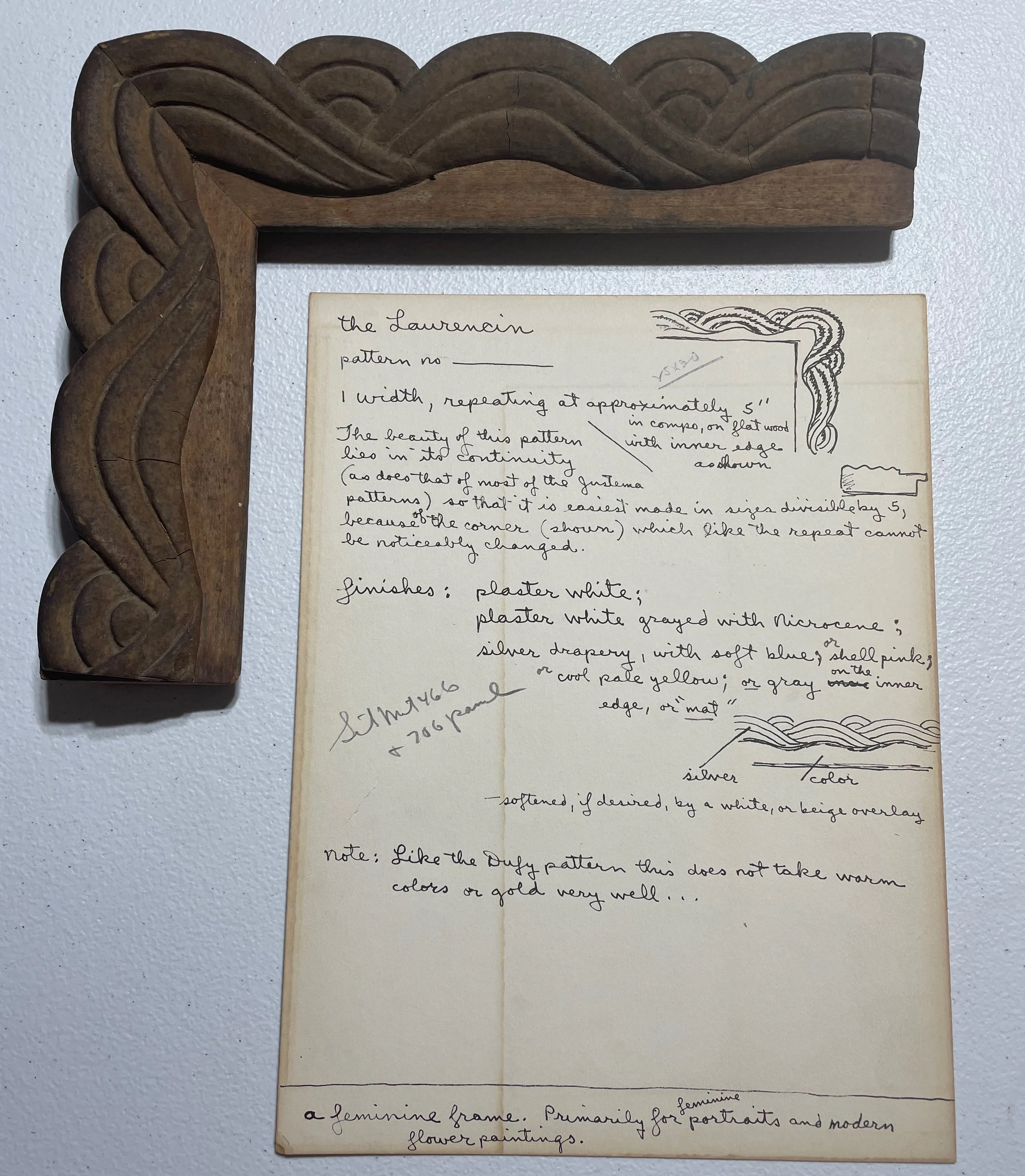

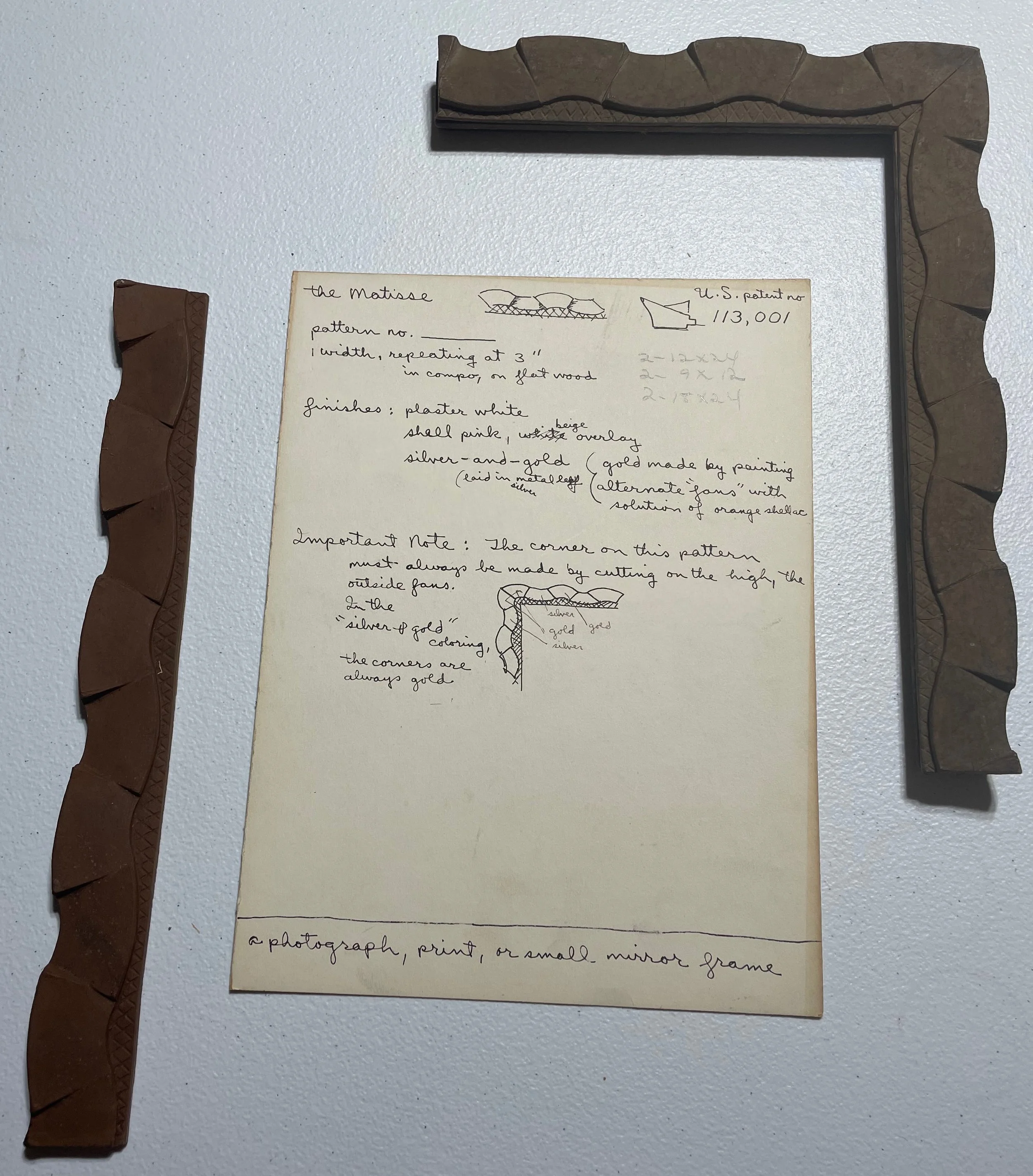

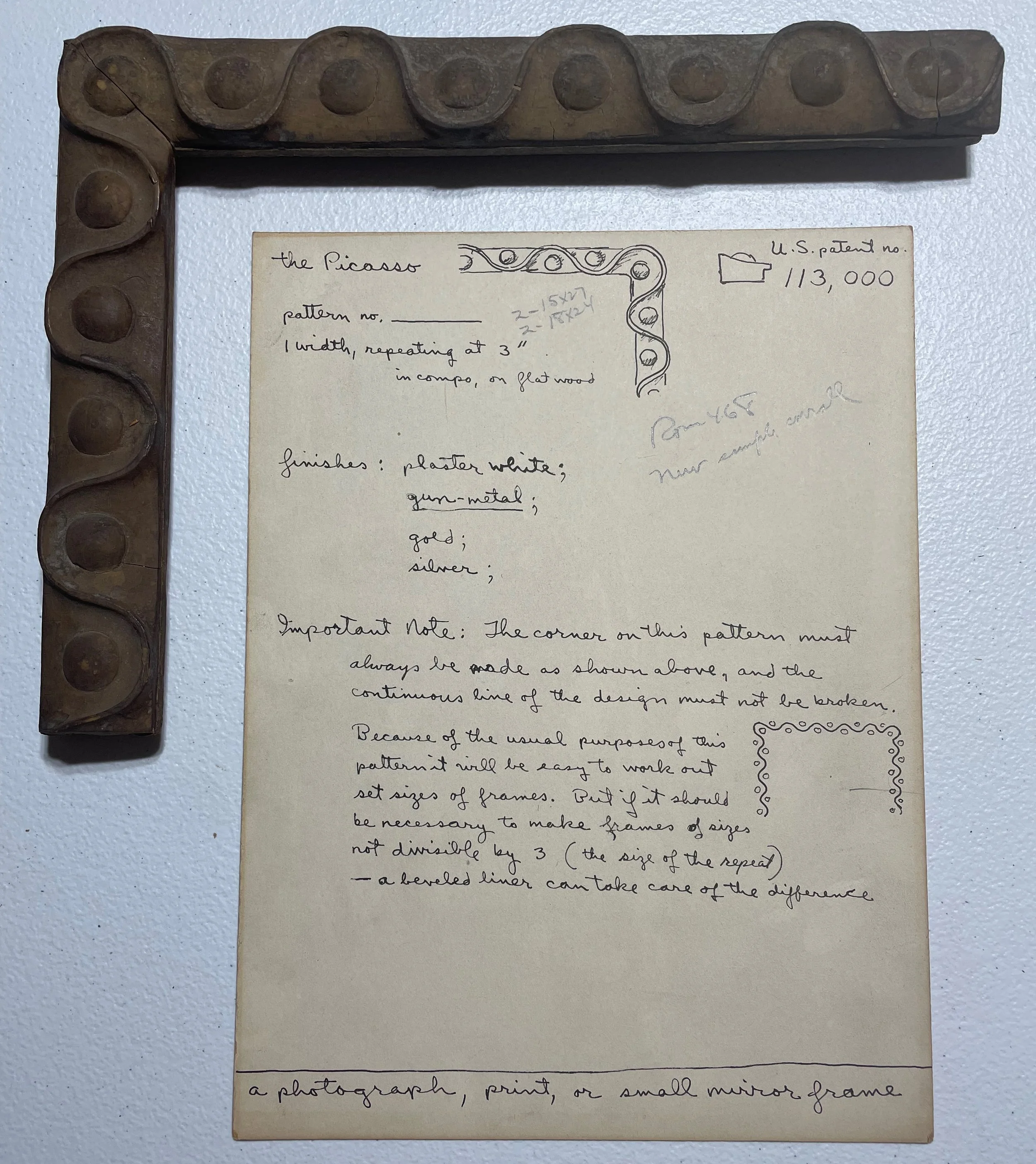

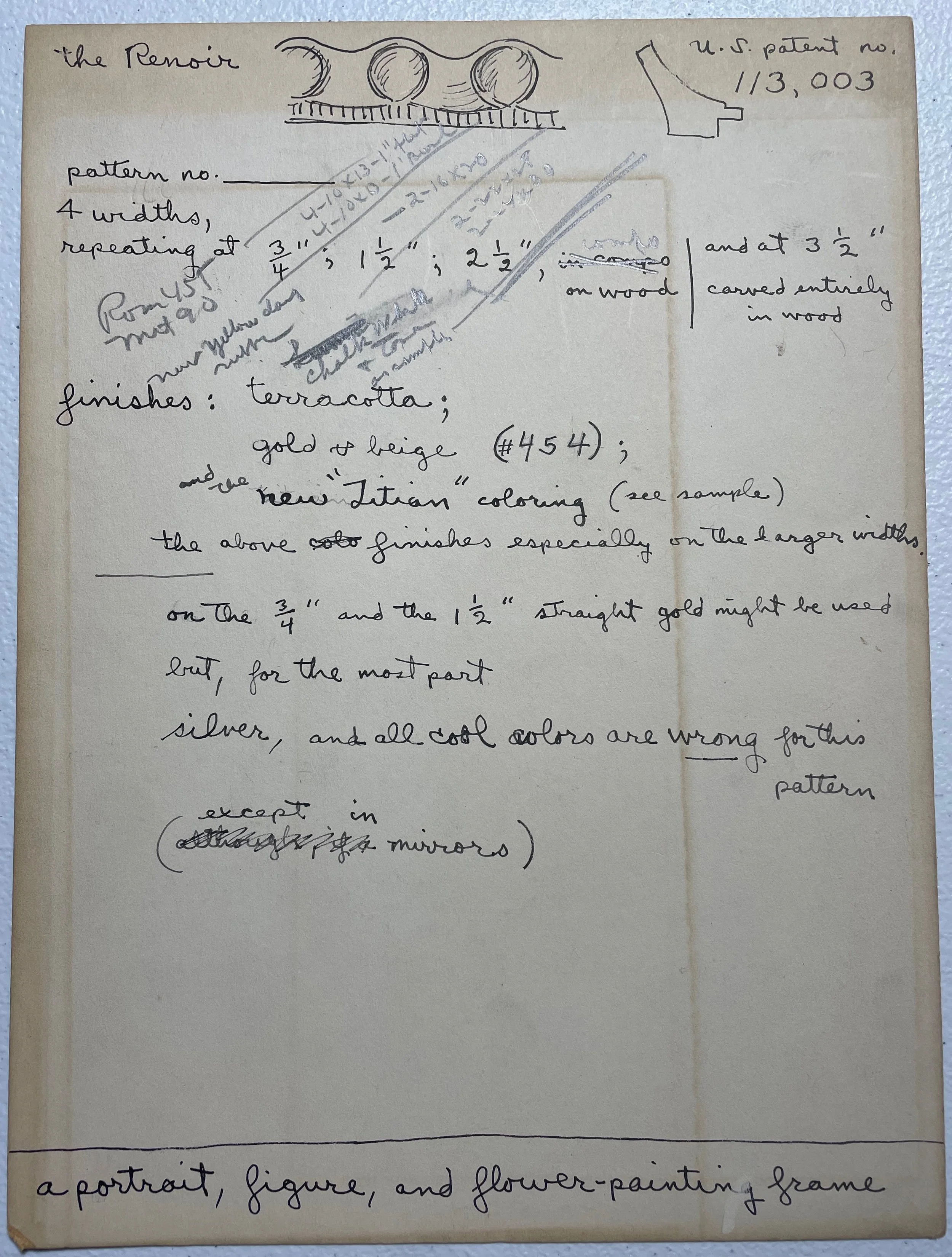

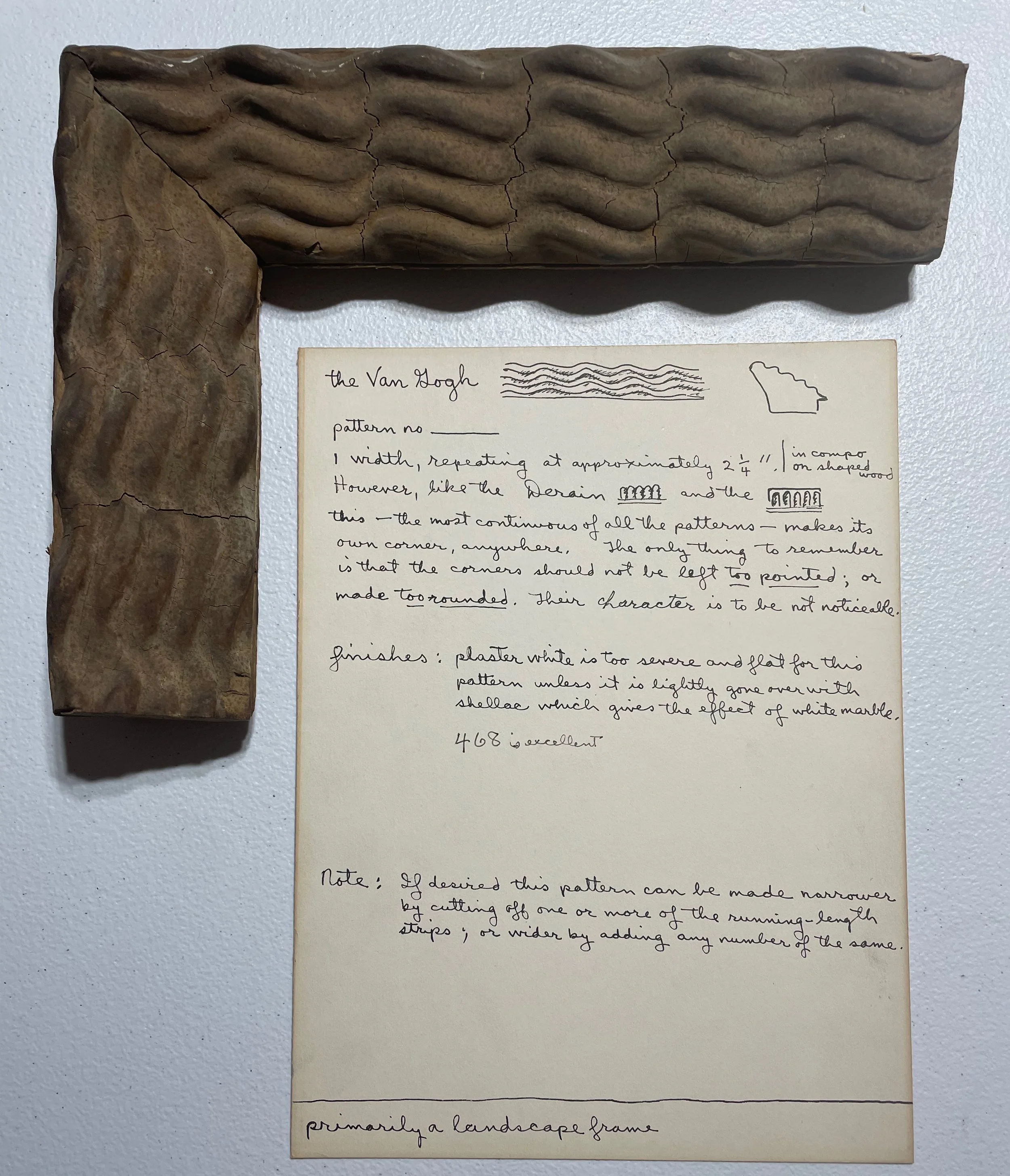

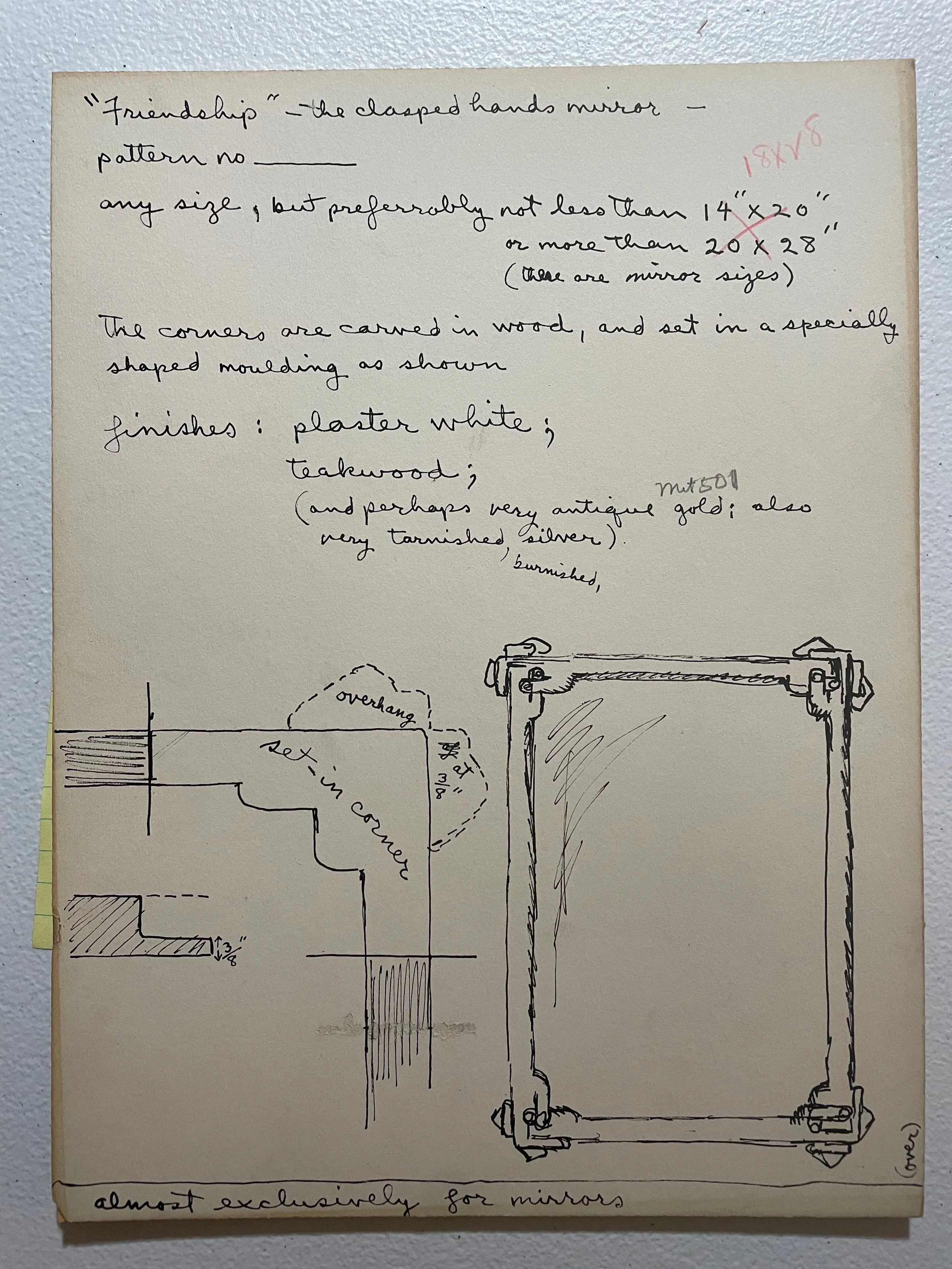

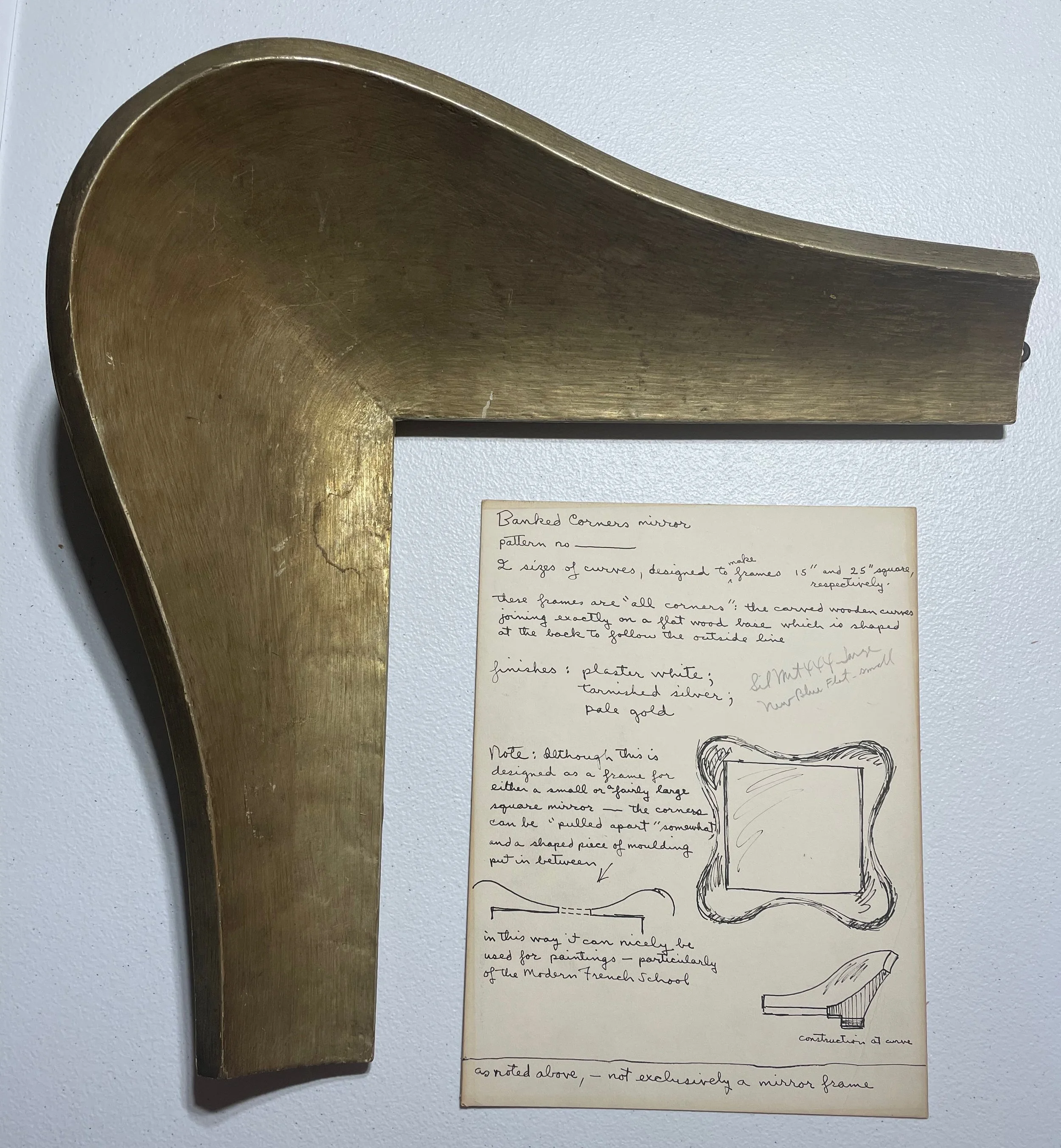

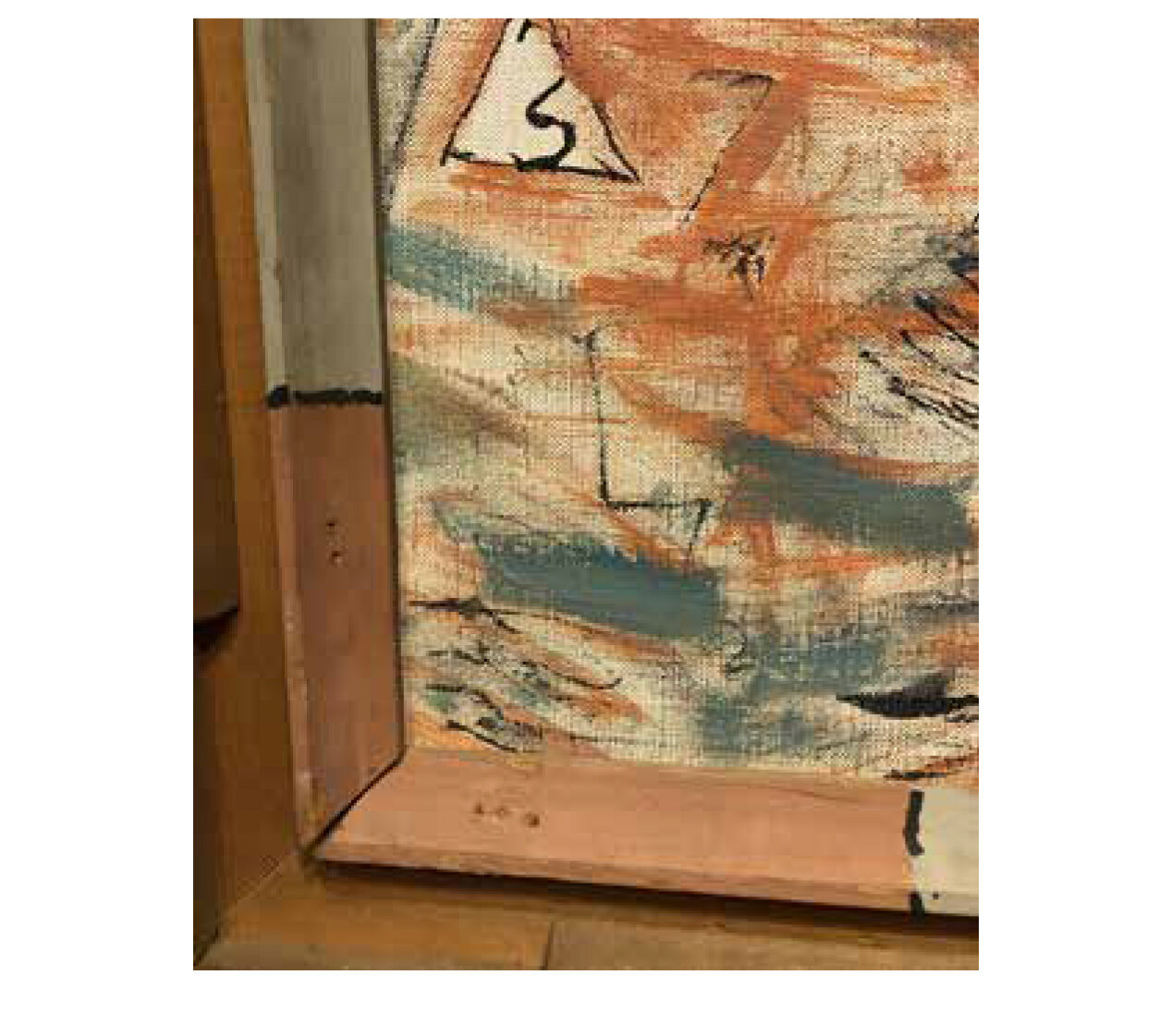

Originally studying painting, in the 1930s Justema focused on frame design. He worked first in San Francisco, California for the Couvoisier Gallery. As early as September 1930 a note in the San Francisco Examiner describes an exhibition of crayon drawings by Justema on view at the Courvoisier Gallery and notes “the plain silvered frame, made by the artist, forms part of the composition.” In the early 1930s he made his first trip to New York and continued to travel between Los Angeles, San Francisco and New York for the next ten years.

Figure 3: Justema in New York City, photographed by Carl Van Vechten, March 4, 1937. Carl Van Vechten Papers, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, MSS 1050.

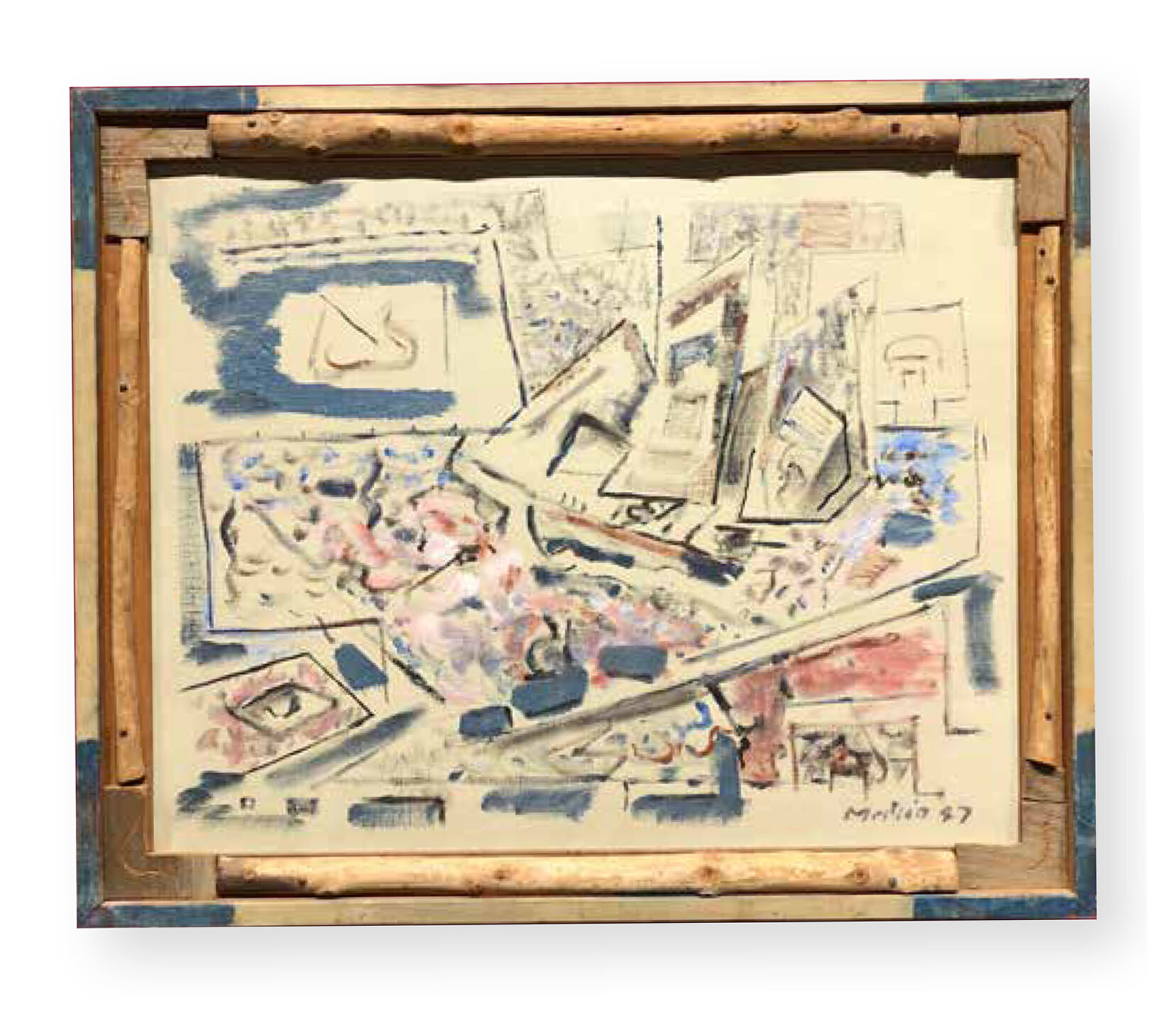

In the mid-to-late 1930s he worked with the F .H. Newcomb Company in New York to produce and market a line of unusual frame designs. It was during this time that he had a space within the Julian Levy Gallery on East 57th Street as a show space for these frames. The effort appears short-lived; in May 1939 he would write to Carl Van Vechten that he would be leaving New York to take a position as a “sculptor-designer with a big display fixture-and-figure factory in Canton, Ohio” and that ‘this showroom is to be mine no more”. World War II soon exerted itself and Justema enlisted in 1942. Serving in the Army 1942-1944 he wrote poetry and published ‘Private Papers: Poems of An Army Year” in 1944.

By 1951 after a 4 month trip to Italy, Justema seems to turn away from frame design and New York and would live in Salem, Oregon and San Francisco for the rest of his life.

Figure 4: Justema in San Francisco, c.1980. Photograph by Judy Dater.

It was in Oregon that Justema met and married his wife Doris Bowman (1905-1977) in 1953. Ultimately devoting himself to pattern, and textile and wallpaper design, he wrote three books on pattern, ornament, and color theory in the ensuing years: The Pleasures of Pattern (1968); Weaving and Needlecraft Color Course (with Doris Justema), (1971); and Pattern: A Historical Panorama (1976).

Justema died in San Francisco, January 1987. [3]

For a discussion of the frame designs Justema marketed in New York City in the 1930’s see the following blogpost ‘William Justema Part II- His Frames’

[1] Several years ago, as a frame company was closing their business, Chip Doyle of Cincinnati, Ohio presciently rescued samples and archival materials otherwise destined for the trash. Among the materials are the samples and sketches by Justema for his frame designs from the 1930’s. It is due to Chip’s generosity that I was able to examine, study and photograph these materials.

[2] Justema wrote a lengthy essay about Margrethe Mather for the Center For Creative Photography, The University of Arizona, Tucson journal (Number 11, December 1979). A memoir of his friendship and time with Mather, the article offers extensive information regarding his own pursuits during the same time.

[3] Interestingly, Justema’s January 9, 1987 obituary in the San Francisco Chronicle states that Justema “spent several years as a monk in a monastery in Oregon”. In conversation with the librarian at the Mount Angel Abbey in Saint Benedict Oregon I have learned that Justema was never a monk. That said, he was a resident artist at the abbey and organized a highly successful religious art exhibit there that was covered by the Capital Journal of Salem, Oregon February 10, 1954.